It has been a busy few months and my curiosity for new things often outpaces the part of me that feels competent enough to share my experience. I just love learning new things and don't always slow down enough to leave any evidence.

However, slowing down to do some writing has been a great way to develop a deeper understanding and generate better questions to explore. This post will be rough draft of some ideas I've been kicking around.

Recently I bit the bullet and have been learning ROS2, the Robot Operating System (v2). It is a vast and abstract ecosystem for developing / simulating / operating robots that very quickly makes you realize how limitless the possibilities are. Then you realize that is a huge problem. There are a million ways to do the same thing - no "right" and "wrong" way but instead "preferred" solutions and then heaps of bad ideas that will eventually cause problems.

Let's start with the bad news.

Three hard truths

Here are the top three reasons that caused me to avoid learning ROS for as long as I have:

- Steep learning curve

- You don't always need it

- It is constantly changing

Unfortunately I think I've now learned firsthand that all of those are true, but somehow I'm still pretty interested.

Architectures

I needed to break down my understanding of how, practically, robot architectures are setup. I considered using the word project ( too generic ), topography ( too geeky ), but I just mean the layout or setup of the various components required to operate a robotic system. This is not an academic exercise as much as it is practical.

I'm going to use my balancing robot as the common thread through all of these examples.

1 Joysticking

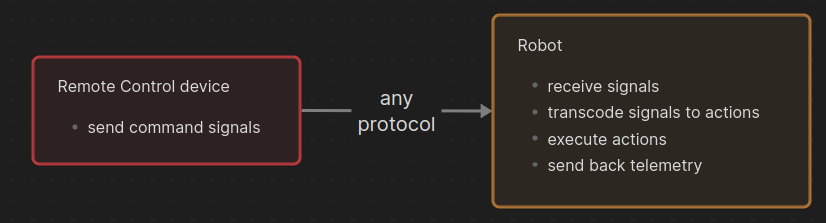

This is the simplest to understand, just think of a "remote control" car or airplane. The robot and the transmitter are two components, each equally uncomplicated. The transmitter sends signals, the robot receives signals and translates them to physical actions like driving.

The pro/con comparison to this setup is completely apples and oranges, but it is awesomely simple.

This is the KISS principle solution. If you want reliability and low technical overhead above all else, this is the way to go.

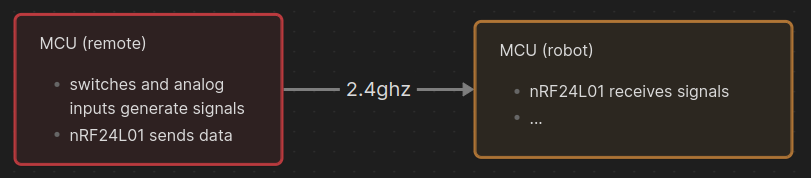

The remote control can be almost anything and using almost any protocol as long as these two components are "paired", or setup to know each other and work together. It can be two arduinos using nRF24L01 radios where one sends instructions and the other one executes them:

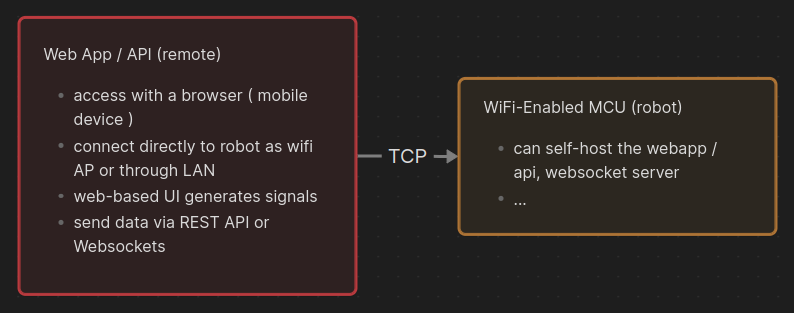

Or it can be a "soft remote", where a web app is used via a web browser and the instructions are relayed to the API exposed by the robot. If the robot provides the Wifi access point and self-hosts it's own remote control application then this is still a standalone system. So it requires slightly more capable hardware, but still just a point-to-point setup:

I've built many HTML-based, bare-bones control interfaces and they were all ugly. The good news is that you can now outsource that effort to AI since it is really only useful for high-level commands.

But you can't interactively control a robot with any real resolution using this kind of interface.

2 Smart / Dumb ( insert less offensive title here )

In any project I feel that there is always one "main" node where most of the computing resources are available, acting as the brains of the operation. It is often onboard the robot itself, or more likely offboard if serving as a hub to multiple robots. I think this used to be called a ROS "master", but I'll call it the brains. Alternatively, sometimes there is more of the 'execution end' of a project where the majority of computing power ( if any ) is dedicated to doing robot stuff. This is everything but the brains, and sometimes there are advantages to it being remote from its brains. How much intelligence lives on the edge?

The question of where this main brain should be physically located is where I get analysis paralysis. There are a lot of trade-offs to consider and this is where the balancing robot example has been educational.

A balancing robot uses an IMU sensor to detect the amount of correction needed to be 'balanced' and turning that into motor commands to achieve that balance. For this to be smooth and graceful means it is running this process many times per second. It would be unacceptably slow and simply unnecessary to 'offboard' this processing task to a remote ( over-the-air ) node for processing. This robot really needs to handle the balancing thing locally.

The great news is that my robot can do this! The ESP8266 has plenty of processing power to handle this task onboard. This is more-or-less the state of progress on the robot right now. It will balance, even if you poke it - not too hard. However, there is no way to control it otherwise. You can't actually "drive" it yet, and this is where I was stuck for a long time.

I finally learned that what I was facing was called a control fusion problem, where two separate controllers (balancing + movement) must be combined to get the desired output. It is like saying, "walk around the room without falling down". As humans we take the "without falling down" part for granted. I am going to similarly force the balancing logic down to the lizard-brain level of the onboard hardware.

So that is to say:

what the robot needs to do = where I want it to go + not falling over

I will only be providing instructions on where I want it to go, while it has to worry about how to do that without falling over.

Enter ROS2

This is the crossroads where the robot I've built so far and my plans for it will hopefully dovetail into a way to learn the ROS framework. I should point out that this architecture pattern I'm describing doesn't require ROS, but integrating with the framework has really helped me organize my project ( and my thinking ).

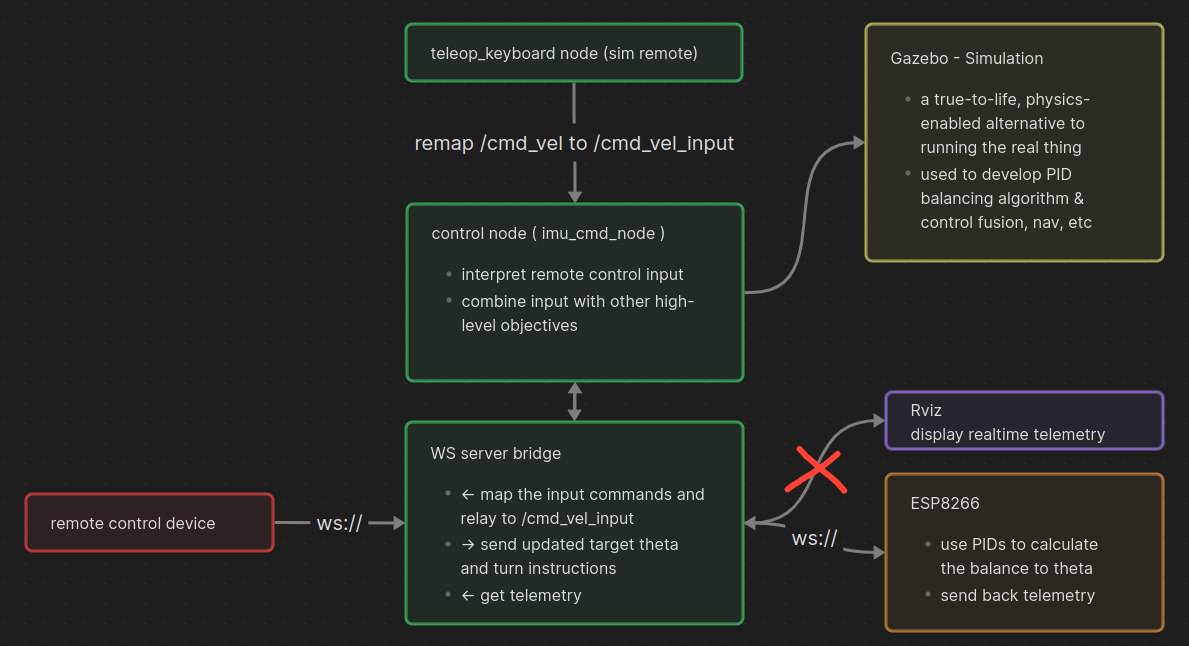

The physical robot itself will not be be "running ROS". I don't think I want to upgrade the hardware on this exact robot - I would need to have at least an ESP32 to run micro-ROS ( which looks hard to do anyway ). I'll save that challenge for another project. This robot will still be commanded primarily via a REST API, and transmit telemetry via websocket. I'll admit that I just don't want to change a lot of this. I actually think dealing with the mixed/bridged protocols is probably a realistic learning experience.

So what is running ROS? Initially I setup a model of my robot for Gazebo which was helpful as a placeholder for the real thing ( seen above ). I probably don't have very good parity between my simulated model and real robot yet, but it's better than nothing. More on Gazebo another time.

There winds up only being a few small ROS nodes ( green ). The biggest difference here is that another host is required to run the ROS nodes. This has practical considerations so it shouldn't be taken lightly. It obviously adds technical complexity too.

In development / simulation it has been convenient to use the keyboard as my "controller" ( the teleop_keyboard node ) and the Gazebo simulation as my "robot". In a real scenario a better web-based control UI could be provided and the real robot hardware used. Being able to modularize and interface these parts is another benefit of organizing this using a framework.

It does all seem kind of like overkill when it would be simpler to just directly connect to the ESP8266 wifi with a remote control client device and send it tilt commands. So this project barely qualifies as benefiting from ROS, but leaves the door open to do more advanced navigation. I did get a lot of value out of setting up the gazebo simulation and experimenting with implementing control fusion.

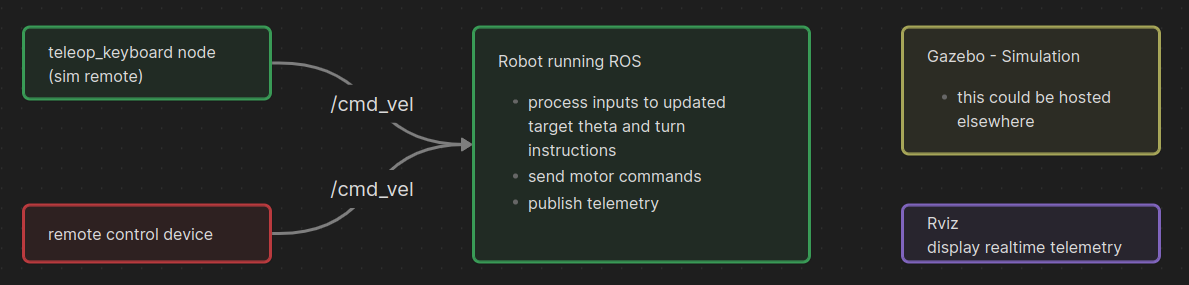

3 onboard brain

The next big jump would be flipping the paradigm and shifting the brains onboard. This is not to say that it is 'autonomous', but it could be. This pattern isn't specifying anything about the autonomous capabilities of the robot, but just that the majority of the brainpower is traveling onboard. The controller directly relays commands to the brain, where the higher and lower-level processing tasks are handled.

I think that is the distinction:

Does the robot carry the higher-level computing and processing power onboard, or just enough to handle a few real-time tasks and execute instructions?

That question is really hard to answer and has direct impacts on the hardware and software side.

In the case of my robot, this would mean running ROS onboard the robot itself and that would require a more capable onboard computer. I'll cross that bridge later, but here is how the diagram would look.

Ask Yourself These Questions Early

When it comes to the physical distribution of the computing components:

- Are the brains onboard, offboard, or a hybrid? Brains are hard to relocate

- What does the control interface look like?

Practical considerations

- Network availability in the field - who is providing the network?

- how many systems require power - the fewer batteries to manage the better